Saving the soul of veterinary medicine

An appeal to practitioners to sustain small, independent clinic ownership

Last June, I attended my veterinary college reunion (45th!) in Ithaca, New York. Over three days of perfect weather, old memories and old acquaintances were revisited and renewed in all their youth and splendor.

Before, during and since that glorious weekend, I have enjoyed ample opportunity to ponder my veterinary career with all its twists and turns, what-ifs and why-nots. I have spent many moments reflecting on our profession — where it started for me and where I see it now.

It saddens me to conclude that veterinary medicine is quickly losing its soul. I choose this word "soul" because, for me, it denotes a life-sustaining spirit, an inner force of sustenance, a vibrant, glowing core.

For four decades plus, I have viewed veterinary medicine as a singular profession. As practitioners, we treat animals and care for owners. Yes, "we care for owners." Our patients do not arrive on their own. The hand of a human is at the end of a leash or upon the handle of a carrier. Our veterinary-client-patient relationship, our VCPR, relies as much upon the C as it does upon the P. And the C and P don't have a chance of finding fulfillment and the finest care with the V unless a sound foundation of trust has been established.

I rarely encounter the word "trust" when studying veterinary journals, webinars and lectures. How do we establish this fundamental condition as we navigate daily examinations, treatments and client interactions? In my opinion, the sine qua non for gaining trust is forging a personal relationship — a one-on-one, caring, empathetic, honest and human touch.

Where would I look first to discover this foundation of trust; this genuine outreach of caring? With certainty, the answer is the independently owned, smaller-sized, community-based veterinary practice. The life and blood and soul of veterinary medicine lies in the long-established, solo-owner, hometown animal clinic.

So I'm sad to see that these clinics are disappearing, as corporate ownership, investment venture capital and super-sized juggernauts consume and dominate the present and future of our profession.

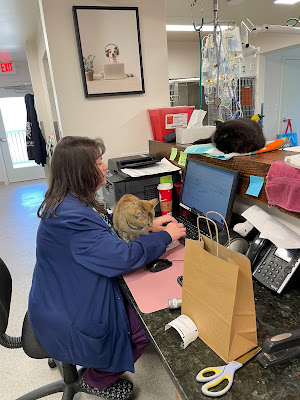

If you have never worked in a smaller clinic such as mine, allow me to draw a picture:

- The receptionists greet each client and pet by name — because they know their names.

- Clients never wait more than 48 hours for an appointment.

- Emergencies are seen that day.

- Appointment requests for specific veterinarians are gladly accommodated.

- There is frequent conversation in the exam room regarding family and all the accompanying health updates and milestones. There is no shortage of bad and sad news; however, we find the time and we have the concern.

More examples of characteristics from my practice that define the soul:

- The veterinary staff and non-veterinary staff have negligible turnover, with tenures averaging 10 years. More than half of the staff has been in place for 20 years.

- Financial concerns and limits are addressed case-by-case, allowing for discounted care when the pet needs immediate attention. If we know the client, late payments may be arranged.

- We see our patients from youth to euthanasia.

- We see our clients age as children to adults, and then we see their children.

- While appointments are scheduled at 15-minute intervals, they often go over — and we do not mind.

- Callbacks are made the next day for every surgery and for most visits involving sick patients.

I cannot view an episode of All Creatures Great and Small without breaking into tears. Silly, right? But the life depicted in the series — which you probably know is based on books by James Herriot, pen name of a 20th-century British animal doctor — is exactly what our profession is losing. These vignettes of a practice that is a family point straight to the profession's soul.

I do not have a Mrs. Hall who answers the office phone 24/7 and cooks all of our meals but I have loyal employees who genuinely know many of the clients as not just pet owners but as friends. The staff is not just staff. We are a family. Having known each other for so long, we truly care for each other.

Don't get me wrong. A large corporate practice will certainly check some of the boxes above, and I applaud them. However, it is my firm belief that the small, independent practice will check more — if not all — of the boxes.

Beyond the trend of large corporations buying up practices is a newer, and in some ways more terrible, trend: Many baby boomers who own solo, independent, small-town practices are reaching retirement. For various reasons, some younger practice owners also are looking to exit. But they cannot find a buyer for their established, vibrant, profitable practices. I speak to such veterinarians weekly who are now contemplating closing the doors and simply walking away.

I am talking about practices that annually gross $500,000 to $900,000. These practices have for years provided incomes that have purchased homes, paid bills, put kids through college, funded substantial IRAs and 401Ks, paid off student loans and provided a comfortable, happy existence.

At one time, these practices would be in demand. They would have associates eager to buy in. The owners might run an ad, and soon, the phone would ring. Simple word of mouth would send someone inquiring. No longer. Why? There are many theories and many new forces at work, but that is a topic for someone else. As these practices serving both small and large animals close, the impact is widespread and devastating:

- Veterinarians lose funds they had counted on for retirement.

- Longtime staff are left jobless.

- Towns lose a clinic, and the next nearest animal hospital may be far away.

- Clients are forced to start over with a new facility where wait times may be much longer.

- A community loses a pillar.

- Veterinary medicine loses another fiber of its soul.

Disclosure: I am among the veterinarians frustrated in trying to sell my practice. But my individual situation is not the problem. The issue is that this phenomenon is affecting a broad swath of clinics.

Please spare me the discussions of EBITDA, no-load and cash flow. I speak to veterinarians who have great numbers but because of proximity to another clinic, the mood of the broker, the high payroll percentage and a million other excuses, they cannot attract even a serious broker.

Is it too late? I say no!

Organized veterinary medicine has a habit of looking at other medical professions for ideas and answers. On occasion, the dental profession has been inspiring. Regarding this very topic, it lends some hope. Dentists have done a remarkable job of maintaining the noncorporate, smaller-sized, traditional community practice. In fact, they are quite successful at passing on facilities to associates and other buyers as they move into profitable retirement.

Where veterinary medicine now approaches 25% corporate ownership and is projected to rise, dentists in recent years have come in much lower, around 15%, judging from a 2021 article in Dental Products Report.

To drill down further (sorry): The American Dental Association — dentistry's counterpart to our American Veterinary Medical Association — has a formal initiative called ADA Practice Transitions (ADAPT) that addresses preserving the independent and smaller dental office. The program has a step-by-step process by which buyers and sellers are connected. Advisers are provided to facilitate the transitions. Simply put, the ADA has decided to play an active role in preserving the soul of their profession.

Perhaps our AVMA would consider a detailed study of the dental profession's trials and errors with ADAPT. Might such a program be of value for the veterinary profession? The AVMA has 400-plus volunteers from every corner of expertise, a professional staff that is surpassed by none, an Economics Division and even a Veterinary Economics Strategy Committee. I would hope that if our association studied this dental initiative and plugged in the unique characteristics of veterinary medicine, we might, in fact, construct our own program.

Considering the present disaster of our disappearing practices, I imagine that an AVMA counterpart of ADAPT could offer significant incentives to encourage and attract reluctant prospective buyers. Among such incentives, I'd suggest including the following:

- discounted sale prices (would a retiring practice owner jump at receiving 80% of practice value compared with nothing?)

- the option of a personal loan carried by the seller, with a minimal required down payment

- providing a list of reputable lenders willing to consider providing the necessary financing

- no commissions for either party (but presumably some type of service fee collected for the association)

- advisers for both parties

- a discussion with the seller of practice management options

- a program in which a prospective buyer first works at the practice alongside the owner and later buys in, either over a period of time or in whole

I would be foolish not to admit that there are impressive benefits that accompany employment at a large corporate facility:

- flexible schedule

- good pay

- health insurance

- paid vacation

- ample continuing education

- mentoring

- human resources support

- fancy, state-of-the-art equipment (read "MRI")

But all of these are standard fare for a practice owner, with the exception of the MRI. Do we all need the MRI?

Here are the benefits of independent ownership:

- being your own boss

- running a profitable business

- holding a recession-proof job

- more wealth

- paying down student debt more quickly

- creating tangible equity

- choosing your own schedule

- hiring family

- amassing a sizable IRA/401K

- becoming a community partner

- mental well-being derived from personal stability and achievement

- saving the soul of veterinary medicine

I was an associate veterinarian for six years. I have been an owner for four decades. I am much happier being an owner! I wonder how many years I would have stayed full-time in the profession had I remained an associate. Certainly not more than 20 or 25 years. And would I have found the success, stability and well-being that I now enjoy?

We are all different, and others' answers to this question will vary. However, I am not alone in lauding the advantages of ownership.

When will veterinary medicine reach its tipping point with regard to corporate ownership? If our profession continues on its present course, we may never see small private ownership again. Without new blood, our soul will slip away, never to be seen again. Just look at our friends in human medicine and their overwhelming corporatization. I contend that they lost their soul a long, long time ago.

One question to which I have no definitive answer is, "How many associate veterinarians have ever seriously considered practice ownership?" If one considers that the AVMA boasts 100,000 members, let's say that 75% are in general practice. That would give us approximately 75,000 veterinarians in general practice. If just 10% are youthful associates who have considered practice ownership, that is a sizable population that we must encourage and support.

Here is my elevator speech to our future, the saviors of our soul:

- Talk to your accountant/financial adviser about practice ownership and its benefits for you.

- Talk to some practice owners, classmates and friends in practice about the benefits of practice ownership.

- If you work at a noncorporate practice, consult the owner about the possibility of buying in.

- Reach out to the "maturing" veterinarians in your town, in your county, in your state. Ask what their exit plan might be. Don't be shy. You might gain some new friends fast.

- Attend your local and state veterinary medical association meetings and spread the word that ownership is in your future planning.

- Don't forget the drug reps as a source for who is looking to sell. They know everyone.

When I finished 15 years of volunteer service on the AVMA House of Delegates and Board of Directors, I promised myself two projects on behalf of the profession: First, write an inspiring book for veterinarians of all ages. That was easy. Within a year, I scribbled down The Happy Veterinarian. Second, and a whole lot more difficult, start a nonprofit that serves to save the soul of veterinary medicine. I founded Veterinary Practice Transition in 2020.

The mission of the organization is to encourage younger veterinarians to consider practice ownership while providing the older generation an option for selling their practice. The nonprofit offers personal loans with low interest rates, a 10% reduction/discount in the sale price, and no commissions for either seller or buyer. The effort is a work in progress. I cannot succeed alone. The profession as a whole needs to address the impending doom.

In closing, let me return to my reunion. As my classmates of '77 gathered and regaled each other with tales of conquest, I saw the immense, reflected energy of careers that served them all so well, but even more, careers that served so many others with compassion and empathy. What I also observed were veterinarians who reached out as family and friend, fostering the trust that defines the soul of our profession.

Mark P. Helfat graduated from Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine in 1977. He owns and practices at Larchmont Animal Hospital in Mt. Laurel, New Jersey. He has volunteered for veterinary organizations and institutions for most of his career (New Jersey Veterinary Medical Association, American Veterinary Medical Association, Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine). Mark and his wife, Mendy, commissioned the sculpture "Shilo" that howls on the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine campus. The couple share their home with four beagles and many cats.

Cheers to you Dr Helfat. Here's to the rest of us working so hard to preserve the many souls vetmed is built upon.

.jpg)

.jpg)